Rock Hard Bodies

an introduction to materials and art

2017

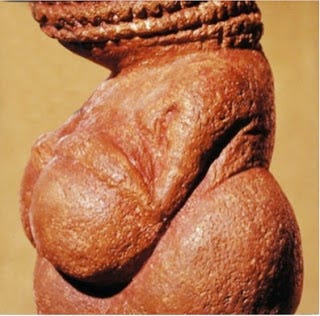

Here is a prehistoric artifact. What do you see? You might recognize a tiny woman, or a penis, testicles, breasts, a goddess, or the Woman of Willendorf. But if we were viewing this from a distance, or if we were holding it, it would first and foremost be a rock. Who thought a rock? Often when we look at artworks we move right into symbolic meaning and miss the most basic meaning: the materiality, the “thingly character,” in this case, the rockiness.

And while contemporary, capitalistic societies generally perceive rocks as “minerals” — inert, lifeless, passive objects, or as commodities to be exploited for economic gain, pre-industrial societies took a different view. Stones were alive, could grow, tell stories, hold memory, draw people together, and could even transform into other beings. Also, rocks were understood not as “minerals”(some western, scientific concept) but as petrified blood, fat, and bones of the ancestors.

Some Amazonian villages consider quartz and other rock crystals to be concentrated semen leftover from ancestral wet dreams. Likewise, in Japan the myth-histories say rice is hardened god-semen delivered to the people through the ancestral land, itself understood as self-hardening, “onogoro,” god ejaculate. The leaders of the Yoruba tribe in Nigeria claim they obtain their red clay from the vagina of the goddess Iya Mapo (and this sheds new light onto humans-from-clay creation myths like the Judeo-Christian one).

Links between food, clay, and flesh are in fact really common in the anthropological literature, as are associations between stone and bone. The Miwok people in California, just one example, are recorded as referring to a white mineral used in healing and body painting as powdered human bone. The mineral is obtained from a hole where the rock giant Yayali is said to have thrown the bones of people he ate. Stone and bone are conceptually linked because they share physical properties of whiteness, hardness and durability. Likewise, ochre is associated with blood because it is red, and when mixed with water looks just like blood. Interestingly, many Chumash and other native California puberty rituals involve women covering their bodies in red ochre and painting red symbols onto large stones. Like men going through intensei physical sundance rituals, women, too, are covered in clay, or in some cases pollen, painted and told to leave it there on the skin for a while. Importatn life moments are marked with minerals, suggesting a human-mineral deminetion that remains in place today, exemplified in various modern-day rituals.

The Woman of Willendorf, pictured above, was supposedly covered in red ochre, and archeologists have found human bones in Europe and in the Americas, in Paleolithic, Mesolithic, and Neolithic burial sites, covered in red ochre, or as we understood it, the healing, petrified menstrual blood of some deity.

I want to emphasize this: in myth-histories around the world, stones can grow, they are alive, and we have to keep that in mind when interpreting stone and mineral artifacts. It turns out that most studies focus on symbolic meaning entirely, and completely overlook the materiality, or rockiness, of the object. They forget Marshal McLuhan’s famous mantra, that the medium is [also a part of] the message.

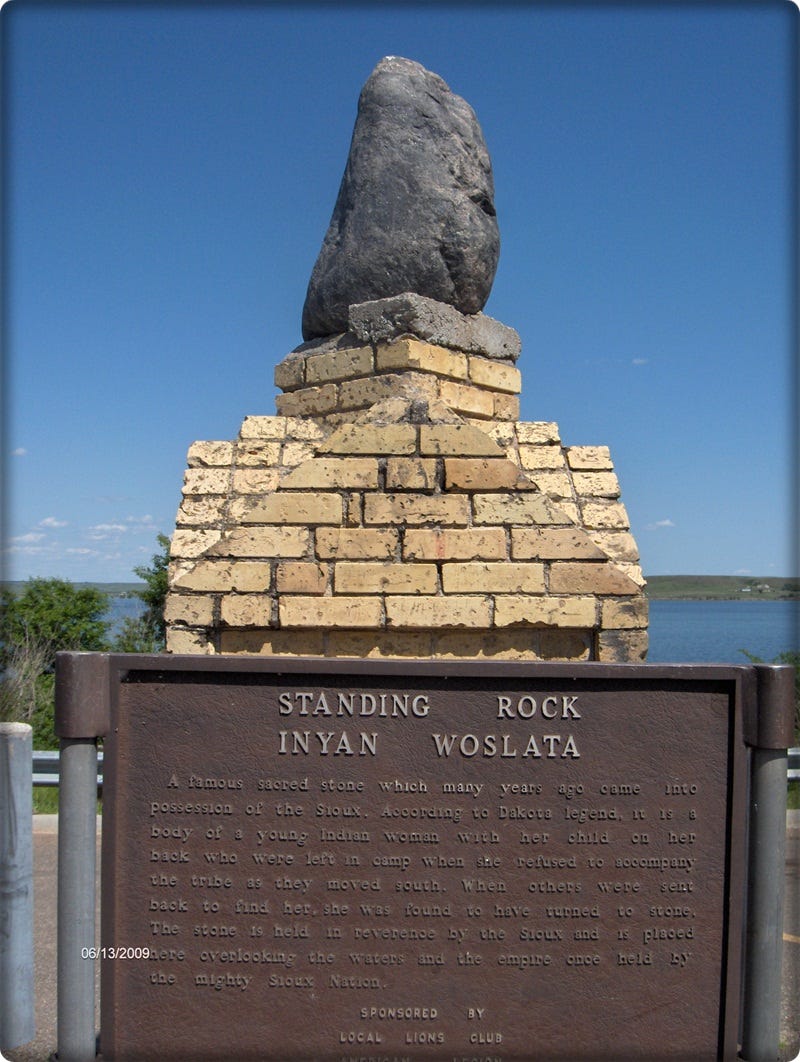

And the medium, in this case, is alive and can grow. Let's just assume that, for fun. There are examples in Australia and New Zealand where stones grow, get pregnant, and have a gender. In Melanesian societies, ethnographers have recorded examples of stones believed to walk around, dance, light fires, transmit and cure diseases, speak, procreate and kill. In Japan, this ancient idea that stones grow is expressed in their national anthem (the shortest national anthem in the world), and arguably in their famous rock gardens. The Chumash people of coastal California describe certain stones as people who turned into stone, and who can sometimes return to their human form. Plains and Pueblo Indians have similar stories. Standing Rock, Inyan Woslata (pronounced ‘iya woslata”) is an Arikara woman who turned to stone waiting for her Dakota tribe to return. The small woman-shaped boulder still stands as a monument marking Standing Rock, SD. Likewise, Lot’s Wife, in the Judeo-Christian myth, turns into a pillar of minerals because she looks back and refuses to move on. I wonder if this is a symbol for that universal truth, that if you are alwasy looking back, then you are frozen like stone and nothing can grow in your salty earth.

In any case, the idea that a cultural hero can shift between human and stone forms is a key to understanding why mountains, rocks and human-modified stone constructions like the Woman of Willendorf, have held so much significance for indigenous people.

Hold that tiny red, seed-like sculpture in your hands. Imagine you are a prehistoric person, and you don’t know where the woman-shaped stone-yet-animate object came from because it was made ten thousand years ago and you just now stumbled upon it within the ruins of a small clay city. It could be a tiny woman who turned to stone and may one day turn back! You better keep her around. Or, plant her in the ground! Just try it! She may grow into a woman, The Magic Seed theory, as some of the clay figurines were planted in the ground (or were they buried?).

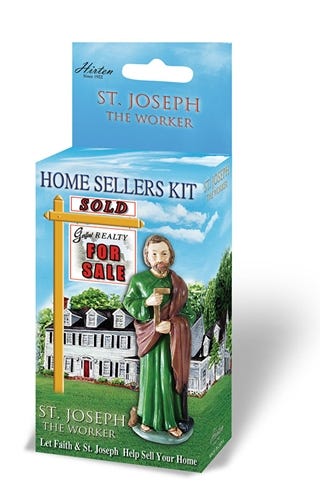

It’s interesting. When my parents were selling their house my mom’s best friend came over and brought a tiny Saint Joseph statue to bury upside-down in the front yard, facing the direction you want to move, or something. Who knows about this American, Catholic, Pagan earth ritual? Is it a cultural retrieval of animism? “Desperate times call for desperate measures.” Is it related to beliefs about making blood offerings to the ground, to appease the spirits under the ground, which is, I might add, an invisible realm more inaccessible than the sky. The world beneath our feet is harder to gaze into than deep space. Remember just a couple years ago scientists found an entire ocean some 400 miles beneath North America. The hidden ocean is apparently locked inside a blue crystalline mineral called ringwoodite, and it holds three times as much water than exists in all the world’s surface oceans! They say this discovery may help explain where Earth’s water supply came from, and how subterranean water affects plate tectonics, and in a way it confirms the Western mythic origins of the oceans, Leviathan, the blue crystal coated water dragon sleeping and stirring inside the planet. There is a great version of the deluge myth from the Jewish Midrash where Yahweh hates people and wants to flood the earth so he takes the small white stone off of Leviathan’s head he had placed there to keep her docile and lets her thrash around, causing water to burst forth from beneath the ground, a scene we saw so beautifully depicted in Daron Aronofsky’s film, Noah (2012). He put the stone back on her head, and vowed to never do that again.

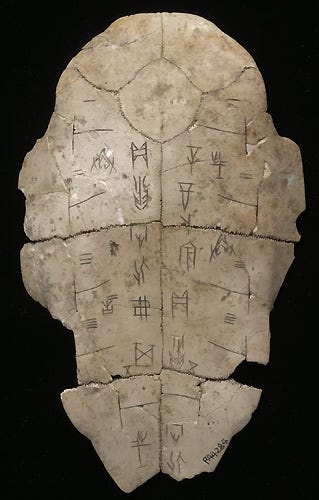

Bone-hard stone is made when clay sleeps with fire. We read in Marilyn Stokstad and Rosemary Joyce that the water left inside many of the female figurines found at Dolni Vestanice made them explode in the kiln. Now why would people so skilled in making pottery — we see they made vessels and clay bricks — why would they purposefully put wet figurines into the kiln to explode? Stokstad gives no answer, but there are three theories, or projections, I like. One is that the artist hated women and wished them harm, treating the clay figurines like voodoo dolls. We can spot misogyny twenty millennia away! Another, and the one that is most popular, is that the artist-shaman used the cracking of the sculpture like the Chinese shaman used the cracking of tortoise shells when placed over heat, or like how the gypsies use tealeaves — as a way to read the future or receive messages from the ancestors. These frozen pictures of chaos and order, these artworks, act like a Rorschach test to reflect back to us something else. The third projection, which I like the best, is that the life of the object recapitulates the life of a person, and destruction is part of the life. The sculpture begins as a small bit of clay, then grows, gradually hardens, and then breaks apart and returns to the ground. I am reminded of the great red terracotta horses in south India. Today, massive red terracotta horses, some of the largest clay sculptures in the world, are built to slowly decay. They are created during rituals where they are believed to be infused with divine life, and then afterwards they are deposited in lakes, or left at the edge of Tamil villages to disintegrate in a process of clay recycling. Likewise, beautiful pottery shards found in burial mounds all over the Americas point to a similar practice of destroying the clay artifact as a way of completing it.

I think Indian clay horses, Standing Rock, Lot’s Wife, my mom’s St. Joseph statue, and the mysterious realm beneath our feet all inform our interpretation of prehistoric art. There can be connections across time and space because everything is source material. Nothing is out of bounds. Do we want to know what these objects mean to us today, in a museum sense, or do we want to know what the objects meant to the people who created them? Maybe we want to unlock the power of these objects to move culture forward through time? I believe that the imagination is an opening onto the collective unconscious, and maybe even onto the prehistoric body from which all human culture springs. We no doubt touch the ground and bones we share with the dirt and soil and animals, even if we are also locked, in some sense, in our colonized projections. The culturally, historically situated meanings we bring to the objects mingle with the basic, boney, stoney, “thingly” materiality of them. If we give our imaginations plenty of material to work with, patterns emerge, and we can receive deeper, more complex and chaotic interpretations of these objects.

Selected References

Ballard and Goldman, (1998) Fluid Ontologies: Myth, Ritual, and Philosophy in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea. Bergin and Garvey, Connecticut.

Boivin, Nichole and Owoc, Mary Ann. 2004. Soils, Stones and Symbols: Cultural Perceptions of the Mineral World. UCL Press.

Chamberlain, B. (1981). The Kojiki. Tuttle Publishing, Tokyo.

Graves and Patai, Hebrew Myths: The Book of Genesis (New York, McGraw-Hill, 1966).

Houtmand, Dick; Meyer, Birgit, (ed) 2012. Things: Religion and the Question of Materiality, Fordham University Press.

Ohnnki-Tierney, E.(1993). Rice As Self: Japanese Identities Through Time. Princeton University Press, New Jersey.